High-altitude tours lead over glaciers, through firn and ice flanks and rocky terrain. A major tactical task here is to weigh up the risk of falling crevices, falling and being carried away and choosing an appropriate and efficient safety technology. Florian Hellberg was involved in the process of coming to terms with the tragic dragging accident in 2017 on the Gabler for the DAV. In his article, he contrasts the backup options at full speed and discusses the advantages and disadvantages.

An article by Von Florian Hellberg - first published in the specialist magazine bergundstieg

The question of the optimal safety technology at full speed is not new. Pit Schubert warned in the 1980s of the risk of being carried away when walking on a rope at the same time. Numerous "mountaineering" articles deal with high-speed safety methods. In issues # 96 and # 98, Bruno Hasler and Kurt Winkler advocate more “walking on a short rope” at the same time. Florian König and Arne Bergau present various safety methods in an alpine tutorial in bergundstieg # 105 on the basis of an alpine tour. The dragging accident in the Zillertal Alps with six deaths described by Andreas Schlick and Stefan Stadler in the current issue # 116 calls for tragedy and explosiveness remembered this discussion.

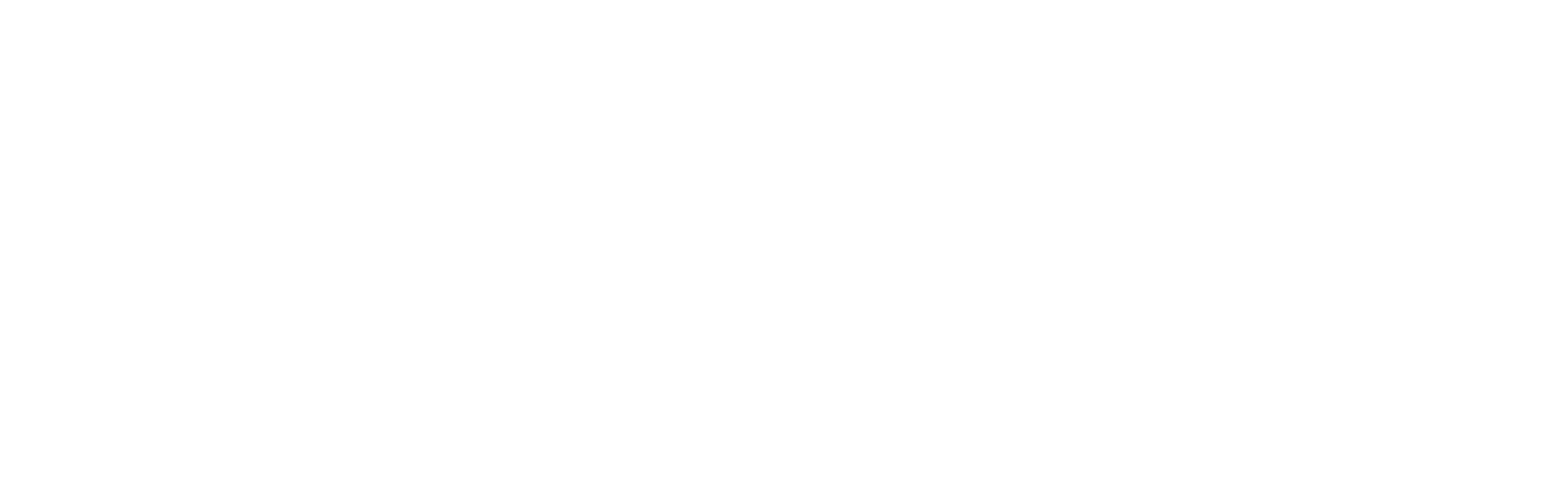

The factors that have to be weighed up against each other when choosing the safety technology in alpine touring terrain are also shown in the DAV accident statistics: If you look at the fatal accidents of DAV members over the past 20 years at full speed (in glaciated high mountains in firn or ice, rocky terrain up to II and on exposed ridges), unsecured falls are the main cause with a share of 28%. This applies even if one does not take into account the proportion of 18% in which it is not clear whether the cause of the crash or heart failure was. The second largest proportion are dragged-away accidents at 25%. Unsecured crevices also play a role, with a 4% share. The question is: what would have happened if those who had an “unsecured fall” accident (who were not traveling alone) had been roped? The provocative assumption: If you walked on the rope at the same time without real safety, your rope team partners would probably have also partly crashed! But: With the application of situationally appropriate safety measures, some of the falls without safety as well as some of the dragging accidents could have been avoided. In the following, therefore, the various possibilities of rope safety technology for high-altitude tours are listed and discussed.

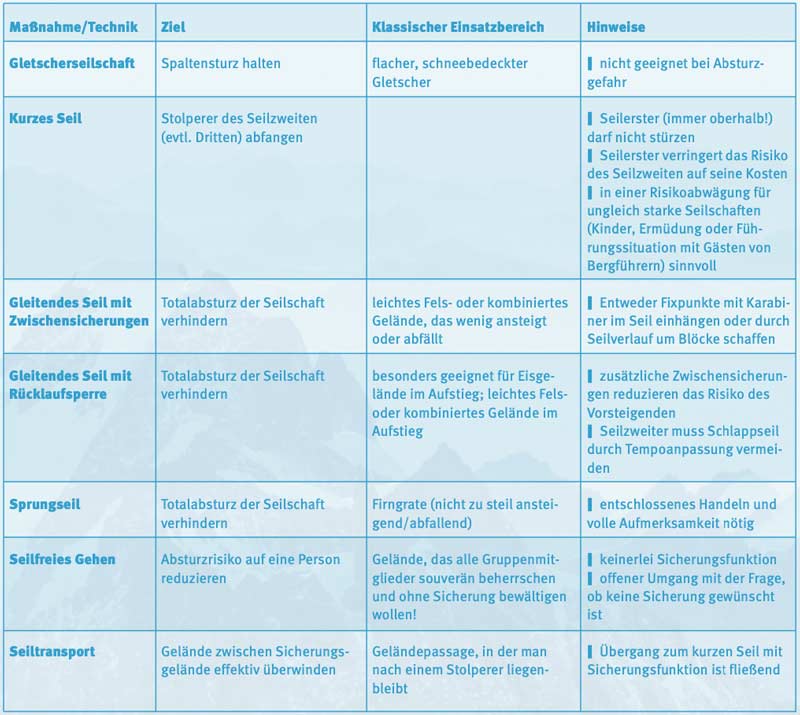

Secure if there is a risk of falling crevasses and if the glacier rope team is at the limits

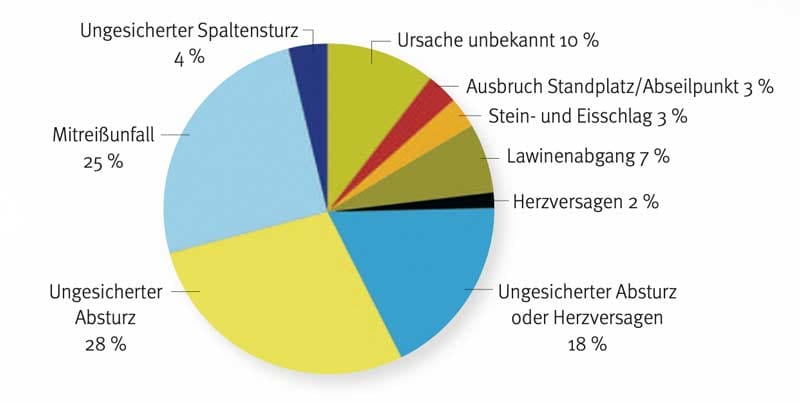

On a snow-covered, flat glacier, because of the danger of falling crevasses, walking around ten meters apart is the safety technique of choice.

There is agreement on this. In the fall area, however, this safety technique is fatal: Especially if the top of the rope team falls, it is impossible for the team to keep the fall, as the person who falls can travel up to twenty meters before the rope tightens to the others in the rope team. Then there is a risk of injury or death by being carried away.

If there is a risk of falling, other securing techniques are therefore necessary. But: when is there a risk of falling? That depends on terrain factors (steepness, slope shape and slope), human factors (weight ratio, personal ability, concentration, equipment, etc.) and the conditions on site (hard or soft snow, ice, good or bad track).

- The harder and steeper the surface, the more difficult it is to hold yourself (or a rope partner) when you start to slide.

- From a slope of 30 degrees, a person who has fallen accelerates almost as quickly on hard snow as in free fall.

- With bare ice or hard-frozen snow, even on moderately steep terrain, there is a risk that you will no longer be able to brake yourself in the event of a fall.

- In the ascent, you are significantly less “prone to misstep” than in the descent.

- A good track is a clear plus in safety. Walking is easier, you don't fall so quickly and you have a better stance to hold the rope.

- Surefootedness, a solid crampon technique, a reasonable speed and a high level of concentration are of central importance. Well-fitting mountain boots, sharp and properly fitted crampons and legwear without tripping hazards are a prerequisite.

Secure if there is a risk of falling

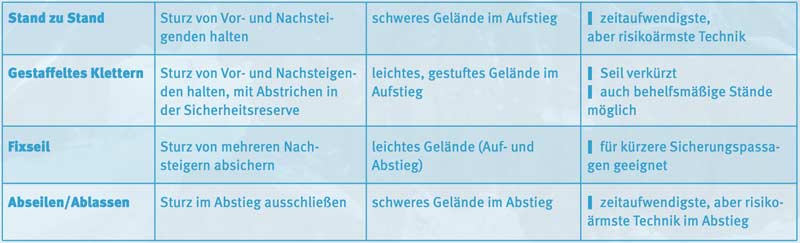

There are several ways to secure in terrain where there is a risk of falling. You can choose from: belaying using fixed points (stand to stand or staggered climbing), the sliding rope, the jump rope or “walking at the same time” on the short rope (with a safety function). In order not to have to waste time stowing the rope between passages at risk of falling in simple terrain, one can only stay roped for “rope transport”. It is of course also a possibility to move unsecured "rope-free". The "optimal" safety technology to be striven for is "sufficiently safe" for the situation and team and "time-saving" in use - including changing the method on changing terrain.

About the author

Florian Hellberg is a member of the VDBS mountain guide teaching team, spent 11 years with DAV safety research and now works as a mountain guide and for the Edelrid company in the field of research and training. (Image Julian Bückers - julian-bueckers.de)

Securing via fixed points

Securing from stand to stand makes sense in heavy rock or ice. In a rope team of two or three, one climbs forward with intermediate belays. Backup is carried out from the stand; Two second climbers can also be secured with a rope switch.

Staggered climbing can be useful in easy, structured terrain. The rope is shortened to 20 to 30 meters. One of them steps forward, if necessary with intermediate securing, and secures the following climbers on a makeshift stand. Makeshift stands can be fixed points that hold downwards such as head loops or, under certain circumstances, body protection, namely with excellent stability (e.g. standing on the other side of the ridge or around one Rock tower around).

If there are more than three people, the fixed cable caterpillar is a sensible alternative for such terrain. Here the rope team leader climbs up to the stand, the second climbers secure themselves with Prusik or rope clamps on the fixed rope.

On the descent, abseiling or lowering over a fixed point would be the safety technique to overcome difficult terrain. Belaying or abseiling over fixed points offer great safety, but are time-consuming - and the more so, the less practice you have.

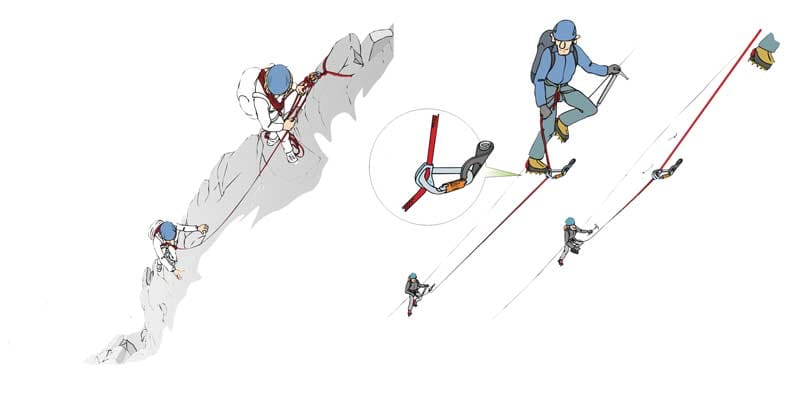

Sliding rope with backstop

Typical areas of application for this technique are steep bare ice passages on the ascent. The rope team leader steps forward (if possible the entire length of the rope), if necessary with intermediate safety devices, hangs a backstop in the rope from a fixed point (as solid as possible) and climbs further. When the rope is off, the second climber (or a maximum of two) climbs up at the same time as the lead climber; The backstop holds back a fall from a secondary climber. This is faster than securing from stand to stand, as several backstops can be used to climb longer distances at the same time. Communication between the leading and following climbers is very important (information given before unhooking the backstop from bottom to top) and the rope team must be able to master the terrain well. Because the technology can only prevent a total fall, in the event of a fall, injuries - probably for both climbing partners - are as good as inevitable.

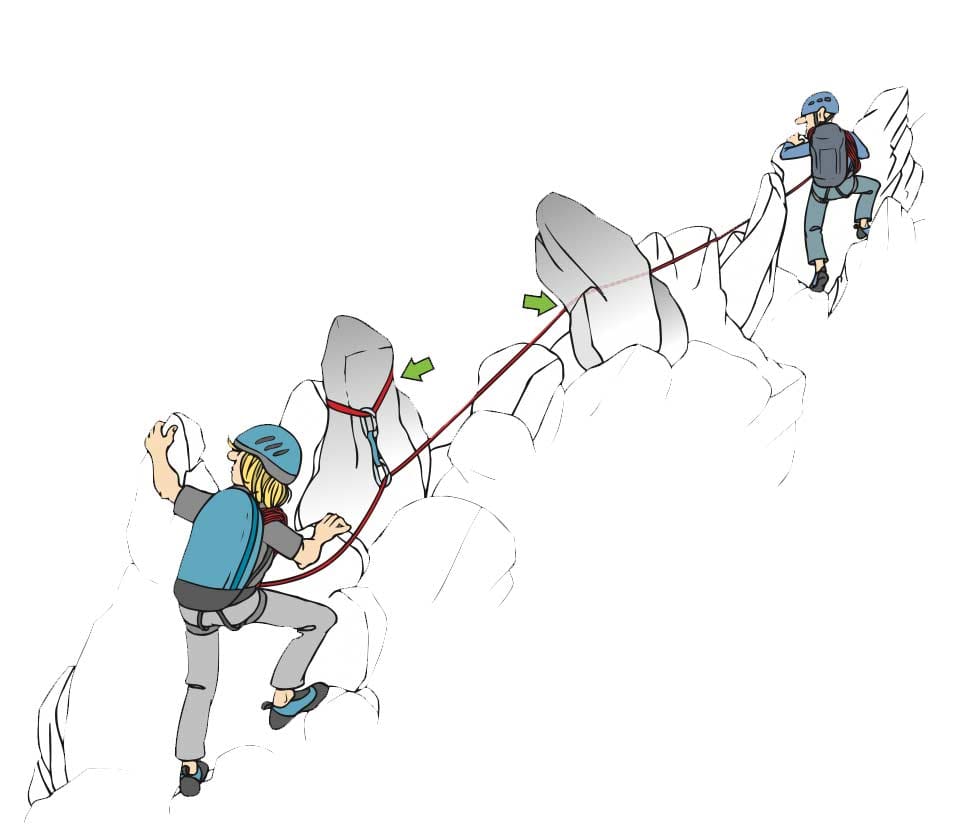

Sliding rope with intermediate securing devices

This technique is mainly suitable for simple rock ridges. The (two) rope team climbs at the same time and between the rope partners there is always at least one fixed point (better: two!) Hung as an intermediate safety device or the rope is laid around terrain structures. Usually it makes sense to shorten the (single) rope to 20 to 30 meters or to use a half rope twice. The technique is relatively quick, especially when both members of the rope team can lead and thus - as soon as the lead climber has used up their equipment - can simply change over at the rollover. Both of them have to master the terrain with confidence; this technique also only prevents a total crash.

Jump rope

The jump rope technique is only possible on pure firn ridges.

In the rocky terrain, the risk of injury and rope breakage is too high. Both members of the twosome have five to eight meters of slack rope in their hands and walk at the same time. If one of them slips off the ridge, the other jumps to the opposite side, thus preventing the rope team from falling completely. The slack rope loops give him a few moments. Determined action is a prerequisite. Especially when cornices force a distance from the edge of the burr, the spurt to the other side is all about survival.

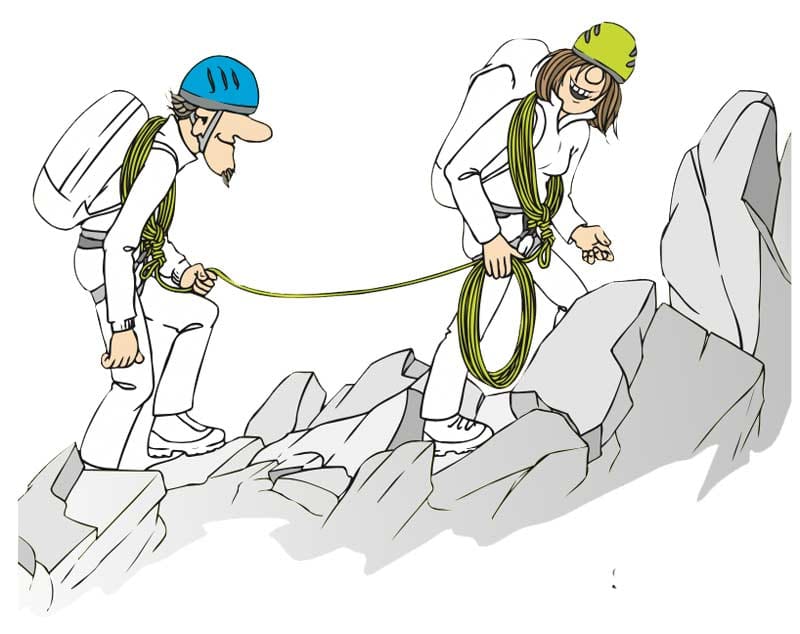

Rope transport

In the safe area between passages where there is a risk of falling, you can only continue roped to the “rope transport”. This saves you time-consuming roping out and roping in between passages in which you are belaying. The rope between the climbing partners is best shortened to a few meters and "transported" over the shoulder in the beam.

Walking / belaying on a short rope

With this technique, the leader and the led walk at the same time, connected by just a few meters of rope. If the person being led stumbles, the leader must quickly prevent it from turning into a fall. In Switzerland, walking on a short rope is also taught for private ropes, in Germany and Austria mainly for state-certified mountain guides. Advantages and disadvantages are weighted differently, there is agreement on the following points:

- The first of the rope (in the ascent and descent of the upper one) must not fall! Because by the time the rope tightens, it has picked up so much speed that it inevitably carries the whole rope team with it. In addition, it must always be superior to the terrain in such a way that it can withstand an additional external force.

- A stumble of the second rope can only be held directly in the approach by the upper one while walking at the same time. If it leads to a fall, then it is probably too late and the rope team is about to fall!

- As a result, slack ropes or too long rope distances are devastating.

- Likewise, the risk of falling increases enormously when walking with more than two rope team members at the same time.

From these points we in Germany conclude that this technique is only an option if there is a clear performance gradient in a rope team and the stronger is willing to accept the higher risk for them. A “leadership situation” arises. In Switzerland, the calming psychological effect of the rope is weighted more strongly - and that when walking without a rope, the hurdle is greater to switch to fixed points in difficult passages to secure. It is also clear: the transition from “rope transport without a safety function” to “walking on a short rope with a safety function” is fluid!

Rope-free walking

The deliberate decision not to use a safety rope is based on a sober risk assessment: The extent of damage is reduced if only one person slips. And: One person alone still has a chance of stopping their slide again. If, on the other hand, a roped rope team has taken off, the members get tangled in the rope and pull each other down. In addition, if only one person crashes, there is still someone who can make an emergency call and / or provide first aid.

However, if you have decided to walk without ropes, this increases the hurdle to later switch to safety with rope. So you rumble without a rope in difficult or delicate climbing passages or in unforeseen difficult places, such as a thin layer of fresh snow on bare ice. Roping up alone is often dangerous because you are standing unsecured in wild terrain. Another aspect is that groups tend to pull apart when walking without ropes and the need for safety of individual group members is not perceived by all. Stronger members in particular are then perhaps in the lead - including the rope in their rucksack ... Stronger ones should be sensitive to this problem and possibly carry the rope in the beam on their body so that it is within reach for securing.

It is not easy to weigh up when walking without ropes is still suitable for everyone in the team. It requires realistic self-assessment, empathy and open, clear communication - like every decision about appropriate safety measures in general!

In practice

In practice, effective security technology consists of a flexible combination of the various methods. For example, when working with a sliding rope and backstops, it often makes sense to secure the last “rope length” using a fixed point. A combination of methods is also obvious when entering an ice wall with a crevice at the edge: over the crevice, the first rope is secured on the ascent with the help of the counterweight of the second rope over a long distance between the ropes. Then you can either switch to a sliding rope with intermediate securing and backstop or subsequent securing via a fixed point.

The requirements for the competence of an alpine tour operator when using such a variable and situation-adapted safety technology are very high! The terrain must be assessed with foresight and the consequences of a possible fall must be assessed. Accordingly, a suitable measure is selected, planned and the risk assessed. When implementing the safety technology, suitable fixed points must be created and rope technical skills must be mastered. This process takes place constantly in challenging terrain and the decisions must also be discussed with the rope team.

Vocational Training

For trainers, therefore, the question arises as to which safety techniques are suitable for which level of participants. On the one hand, useful techniques should not be withheld from the participants. On the other hand, there is a risk of overwhelming the participants. It can therefore be observed again and again that less experienced mountaineers learn and use an "alibi security technique" with the risk of a rope team crash. This can be the case, for example, if participants lack experience in assessing fixed points.

In the DAV trainer training, the securing techniques, which are located between rope-free walking and securing a stand, have come more into focus in recent years. In the high-altitude and ski touring area (in addition to the classic group leadership techniques such as fixed and handrail rope), staggered climbing on the shortened rope, the use of multiple switches or securing with a sliding rope on the block ridge is part of the Trainer C training. For the B-Hochtouren trainer there is also a sliding rope with a backstop in bare ice, a jump rope on firn ridges and a "awareness unit" (practical exercise) to guide one person on a short rope in the descent in the firn. The aim of this awareness unit is on the one hand to show and experience the limits and problems of the short rope, on the other hand to provide a method to be able to offer support to a single person in an emergency (weak people) on firn slopes in the descent (see also the reader's reply from Markus Fleischmann in the last issue). The awareness unit on the short rope was the subject of intense discussion, especially among mountain guides.

In the DAV, an extensive redesign of the alpine trainer training is taking place, in the course of which the techniques between glacier rope team and stand to stand security are to be taken into account even more in the future.

Which techniques from the presented repertoire are trained in alpine tours by DAV sections for club members or in alpine tours by mountain guides is still very different and has not yet been fully discussed. Personally, I think that private alpine tourers should also use a wider range of safety techniques - not least because there are more demanding passages due to the evacuation and retreat of glaciers, even on supposedly “easy” alpine tours.

Securing via fixed points

Notes

- Easy and difficult is not to be seen as an absolute category, but depends on the personal skills of the rope team, daily form and the circumstances.

- The illustration relates to the correct application of the techniques. With all safety techniques with fixed points, their quality naturally decides whether there is a gain in safety or an alibi effect with the risk of a rope team crashing!

About the magazine bergundstieg

Bergundstieg is an international magazine for safety and risk in mountain sports and illuminates the topics of equipment, mountain rescue, rope technology, accident and avalanche knowledge. Bergundstieg is published by the Alpine Associations of Austria (PES), Germany (DAV), South Tyrol (AVS) and Switzerland (Customer Service).

+ + +

Credits: Cover picture Bächli mountain sports. This article first appeared in the journal mountaineering.