Climbing – indeed alpinism – would be unthinkable without carabiners. Nevertheless, the oval hard parts often lead a shadowy existence. Whether HMS carabiners or quickdraws: without them archaic looking things we would fall into the abyss faster than we would like. We take a closer look at the world of carabiners.

A contribution by Fabian Reichle - Bächli Bergsport

Carbine are first mentioned in the 18th century and similar constructions existed before that. The German climbing pioneer tinkered for the sport of climbing Otto Herzog before the First World War with the use of carbines. In alpinism in general, their triumphal procession took place around the turn of the century. A lot has happened since then.

Proven retention

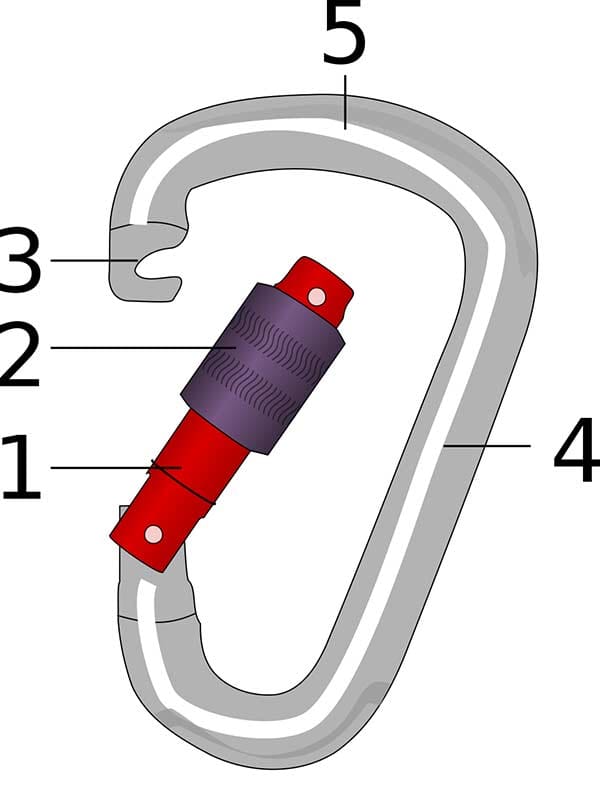

The basic structure of a carabiner is still the same. There is a long dorsal side opposite the one with the snapper. The latter is the part with the opening and closing mechanism. The snapper gets its name because it snaps into the nose of the carabiner. The bow, i.e. the transverse part above the nose, is designed so that the rope can run over it.

With an open carabiner, another expression becomes relevant: the opening width. This describes the maximum distance between the gate and the nose when the carabiner is open. This metric is elementary so that mountaineers can get an idea of how much material the carabiner can hold and how easy it is ultimately to hook. This can be particularly important when operating with gloves.

Not all carabiners are the same

Depending on the application, the shape and resilience of carabiners vary. In order to prevent wild growth, all models are checked according to the DIN EN 12275 standard and the UIAA-121 standard. There is an overview at bolting.eu respectively at UIAA.

In principle and very roughly between normal carabiners, i.e. those with regular snappers; HMS carabiners, i.e. with twist lock safety; via ferrata carabiners and some others. The standardization provides specifications for the breaking load.

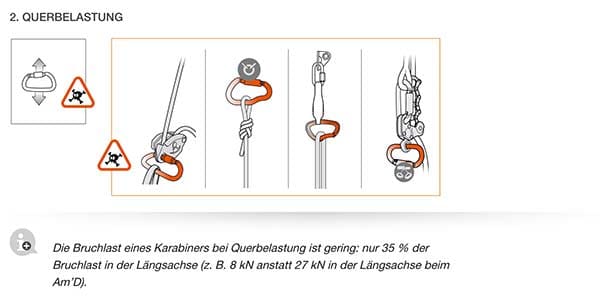

This in turn is divided into three load conditions: longitudinal, transverse and open. The limit decreases in this order. The differences are striking. For example, while an HMS carabiner has to withstand a longitudinal load of 20 kilonewtons, the transverse load already shrinks to seven and even to six kilonewtons when open. Incidentally, one kilonewton corresponds to the weight of 100 kilograms. The HMS carbine must therefore be able to intercept 2 tons longitudinally.

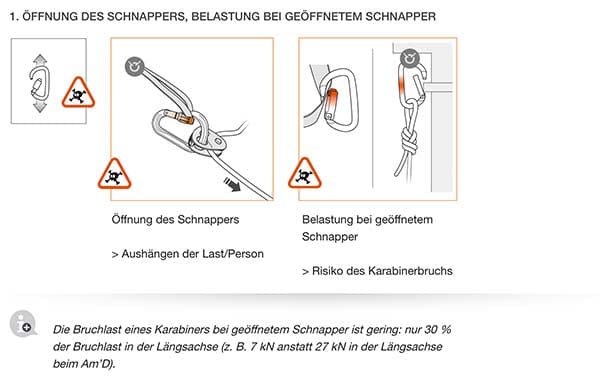

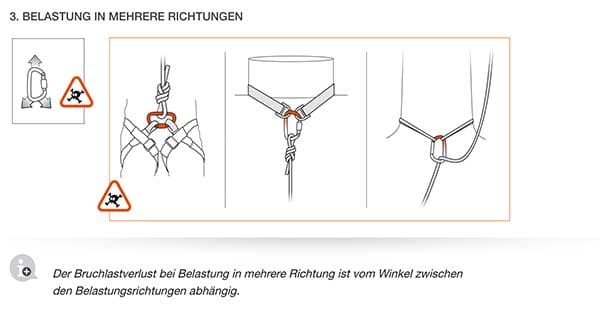

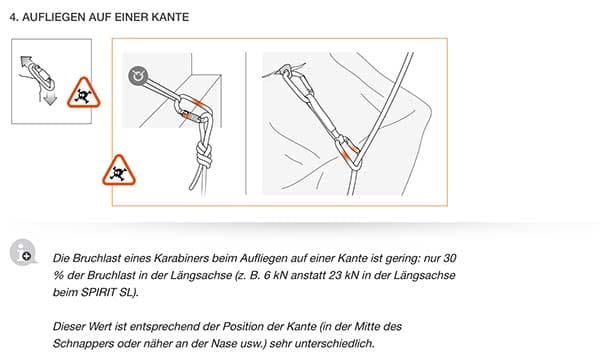

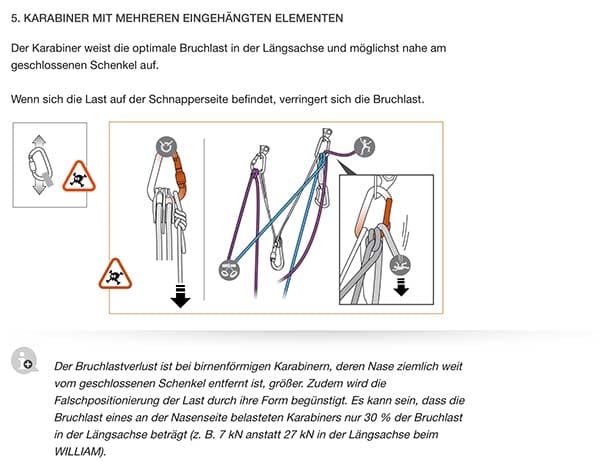

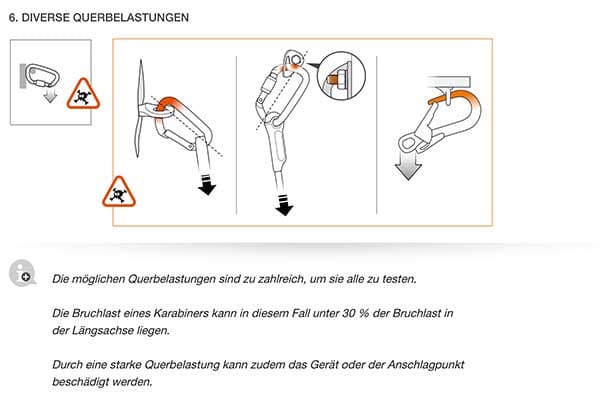

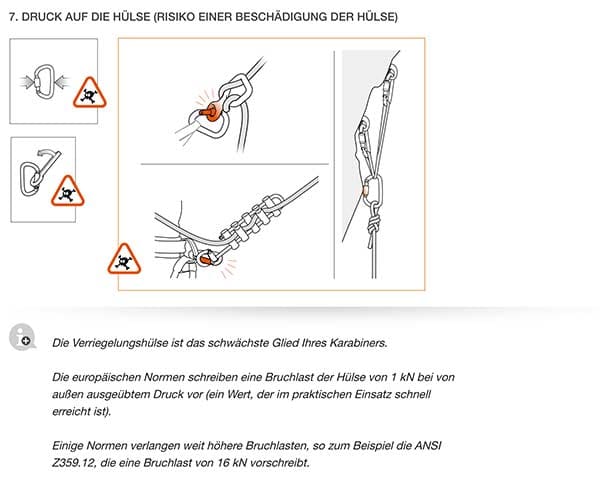

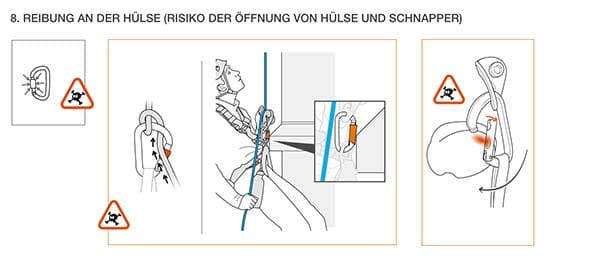

Examples of dangerous loads on carabiners (source: Petzl)

Despite everything: Extreme caution is required when lying down. For example, if a carabiner breaks on a cliff edge. The load can be just as dangerous in several directions. In many of these cases, a carabiner only achieves around a third of the maximum load. Petzl offers a clear overview here.

In addition, a carabiner will eventually show signs of wear and tear and, at worst, become a real knife as the metal edge that the rope runs over becomes worn and sharp. If you also use quickdraws, you should make sure that the connecting material made of Kevlar, nylon or Dyneema is showing signs of age, rather than the carabiners.

Fresh out of the oven

At the very beginning, a carabiner is a stick made of aluminum. And not just any, but so-called 7075 aluminum. This has the highest strength and is also used in aircraft construction and space travel.

This rod is now cut into small parts, which in turn are machined into the rough shape of the desired carabiner. Now comes the most important part: the hot forging. This gives the carabiner its actual appearance.

Remaining excess aluminum is removed, followed by the heat treatment or hardening and quenching, which gives the devices their final hardness and strength. This is done according to the so-called T6 standard. The process ensures that there is improved fracture toughness and resistance to stress cracking and exfoliation.

Video: How carabiners are made

As a literal final touch, the carabiners are made supple in a kind of tumbler with granular inserts. This eliminates any sharp edges. After further mechanical interventions, such as drilling the holes for the gate, carabiners are usually anodized. In other words, an electrolytic process protects the metal from corrosion, which is promoted by weather influences, for example.

Finally, the carabiner is assembled. The gate is assembled and laser engravings are applied. In addition to logos and the like, the latter often also contain important information on load limits. So it's worth taking a closer look at them.

"It takes a year of development plus a certificate, followed by six months of production and shipping from the first sketch to purchase."

Magnus Rastrom

Before the carabiner goes on sale and can be used on the rock face, the sometimes lengthy certification process follows. A year of development plus a certificate, followed by six months of production and shipping, it takes from the first sketch to purchase, explains Magnus Raström, Senior Product Manager Climbing Gear at Mammut.

Innovation at second glance

As mentioned at the beginning, a carbine is a primitive piece of material. In fact. Why then do new models keep coming onto the market? Magnus Raström develops carabiners at the Swiss mountain sports specialist Mammut and knows the small, fine details: “Our modern carabiners use less material, so they are lighter. Nevertheless, the quality of the material increases.»

“Our modern carabiners use less material, so they are lighter. Nevertheless, the quality of the material increases.»

Magnus Rastrom

Ultimately, it's the little things that make a carabiner better than its predecessor. An optimized cable run on the carabiner arch, a revised nose so that the snapper clicks in more efficiently, more sensitive material for optimized handling or an orange marking on the twist lock that signals that the carabiner is not closed are all current innovations from Mammut.

Such developments make sense because there are no compromises with a carabiner. The safer it is, the more efficiently it works and the easier it is to use, the better. It is therefore also worth sorting out your old devices after a while, even if they are technically still usable. It is simply presumptuous to save on security material.

At Mammut, carabiners are usually in the range for around five years - a good rhythm for bringing your own material up to date with product development.

And even if carabiners have a purely practical purpose, they can also be combined aesthetically with the rest of the mountaineering equipment. Mammut is aware of this, which is why Raström gives a glimpse into the internal competencies: "We have carabiners in our range that were designed by the same designer who also designed our backpacks."

That might interest you

- No more neck pain when climbing thanks to safety glasses from YY Vertical

- Storing climbing equipment correctly: tips from the pros

- Five climbing areas above the fog

About Bächli mountain sports

Bächli mountain sports is the leading Swiss specialist shop for climbing, mountaineering, expeditions, hiking, ski touring and snowshoeing. Currently offering 11 locations in Switzerland Bächli mountain sports its customers expert advice and high quality service. LACRUX publishes in collaboration with Bächli mountain sports Articles on the topics of climbing and bouldering.

+ + +

Credits: Cover picture Nikolay Vasilyev