Fortunately, excavators that have been ground in and fixed for a short or longer period of time have so far only rarely led to accidents. But when a rope breaks, the effects are often devastating. We spoke to Daniel Benz, club president of EastBolt, about a danger in sport climbing that is known to many but still doesn't get the attention it deserves.

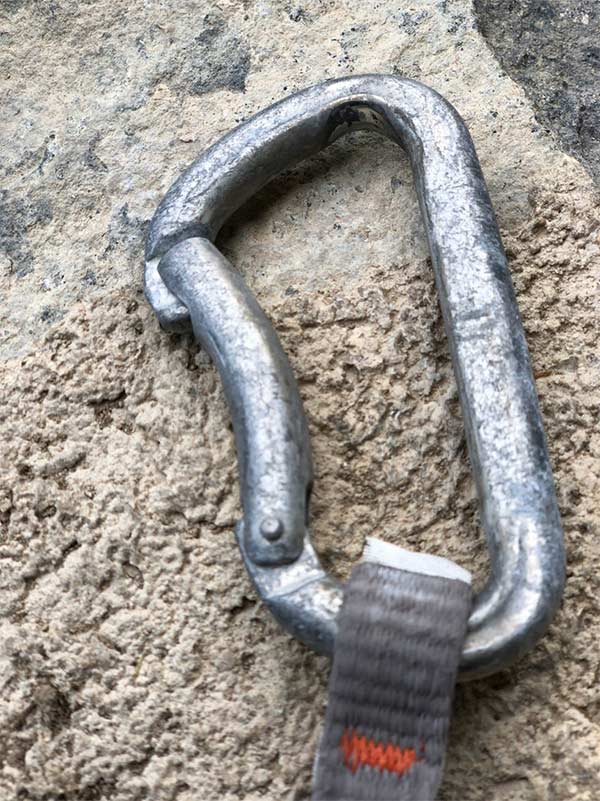

Mark Hutter recently published his thoughts on fixed quickdraws in sport climbing routes in a guest article on the subject of fixexes. His Opinion Article «Fixexen – Will the rock face become a consumer arena?» has been extensively read and discussed. We would like to take a closer look at one aspect that Markus Hutter deliberately left out: the risk ground-in carabiner.

we have with Daniel Benz talked about broken ropes, error culture and personal responsibility. The Sarganserländer has been in the mountains since he was a child and, as a sport climber, often also on routes that are equipped with potentially dangerous fixed ropes. As president of the EastBolt association, he and other passionate climbers and explorers are committed to safety in climbing. The association takes care of the maintenance of existing climbing infrastructure and supports the rehabilitation of routes.

Daniel, why are you joining EastBolt?

In principle it's quite simple: I was asked by Fredy Tischhauser, who made a significant contribution to the formation of the association, to take over the presidency. I didn't know exactly what to expect in this role, but I had my own opinion on the topic of renovation. I used to complain from time to time when routes had lost their experience value and quality due to renovation, and I thought: instead of just complaining, I could really make a contribution and thus have a say.

How often do you encounter ingrained fixexes in your everyday climbing?

Unfortunately, when I climb privately, I often encounter questionable ground-in carabiners. If you enter a route somewhere where fixed material or material left for projecting is hanging with aluminum carabiners, there are usually some that are already at least in a questionable status.

But back to the topic: my perception in terms of fixexes is that there is almost always material hanging on popular, difficult and steep routes. If it is removed, the next person simply puts something back in. I think that you should at least use good material that is not sharpened within a very short time.

"I've already observed that brand-new aluminum carabiners were hanging on a route, and a week or two later they were sharpened dangerously."

Daniel Benz

How fast can this go?

Especially when a lot of people are trying out a route and it is perhaps also long and drags a lot of rope, it can happen quickly. Sand or other fine particles in or on the rope also contribute significantly to the grinding effect. I've seen brand new aluminum carabiners hanging down one route, only to have them sharpened dangerously a week or two later.

A lot has been written about the danger of rope tears caused by ground-in carabiners, at least since the tragic accident in Magletsch in 2012. From your perspective, what has changed since then?

Nowadays, steel carabiners are much more common where aluminum used to be "installed". This means that a certain change has definitely taken place. Incidentally, steel carabiners are not only used outdoors, but also in climbing gyms. Steel carabiners also grind in, but this whole process takes many times as long as with aluminium. It is not the case with steel carabiners that they become sharp-edged practically from one day to the next. If you notice the first signs of wear and tear, you still have enough time to react.

Do you think that overall enough awareness has been raised about ground-in carabiners?

On the one hand, yes, the topic has been widely discussed and everyone can know about it. But when I look around, there are always aluminum carabiners hanging, and - unsurprisingly - sharply ground aluminum carabiners are also hanging again and again. From this I have the feeling that there are still people who are not aware of this danger or who are not sufficiently aware of it.

In addition, one can add here that ground-in carabiners – even if they are not yet sharp in the cutting stage – have a severe impact on the lifespan of ropes. People also punish themselves financially with the "scrap".

“When I look around, there are always aluminum carabiners hanging, and – unsurprisingly – there are also aluminum carabiners that are sharply ground in.”

Daniel Benz

Does the cost aspect also play a role when choosing between steel and aluminium?

I think the cost aspect plays a subordinate role. Availability plays a much more important role, steel carabiners are more difficult to obtain and most don't have any in stock, so as permanent material they just take what they have.

But sometimes it also happens that someone projects a route, equips part of it with good material and mounts the rest from the climbing position each time. Then the next one comes and supplements with material that is qualitatively okay at the beginning, but is not suitable for this purpose and is therefore quickly sharpened.

"It would be nice if a lot of people were aware of the problem and everyone always had a couple of steel carabiners with them. If you discover a sharply ground-in carabiner, you can exchange it.”

Daniel Benz

It can hardly be prevented, can it?

A tip that was passed to me by Marcel Dettling and which I have now adopted for myself: I always use an Exe with a steel carabiner for the first intermediate belay when sport climbing, because that way the material simply lasts longer. When I plan a route for a day with my own equipment, I now prefer to use steel carabiners in places where I often fall or where the rope is severely deflected.

It would be nice if many people were aware of the problem and always had a couple of steel carabiners with them. If you discover a sharply ground-in carabiner, you can exchange it. At this point it should be mentioned that the price for a steel carabiner is around three francs today if you procure it through suitable channels.

"It's still better to take out a sharpened carbine, even if you don't have a spare with you. After all, the source of danger was then removed.”

Daniel Benz

I would even go so far as to say: It is always better to take out a sharpened carabiner, even if you don't have a spare with you. After all, the source of danger has been removed. In the worst case, someone will later pass this intermediate belay and cannot climb due to a lack of their own material. Then you just have to climb back, jump off or climb further without cliffs. It's always better than a possible rope break.

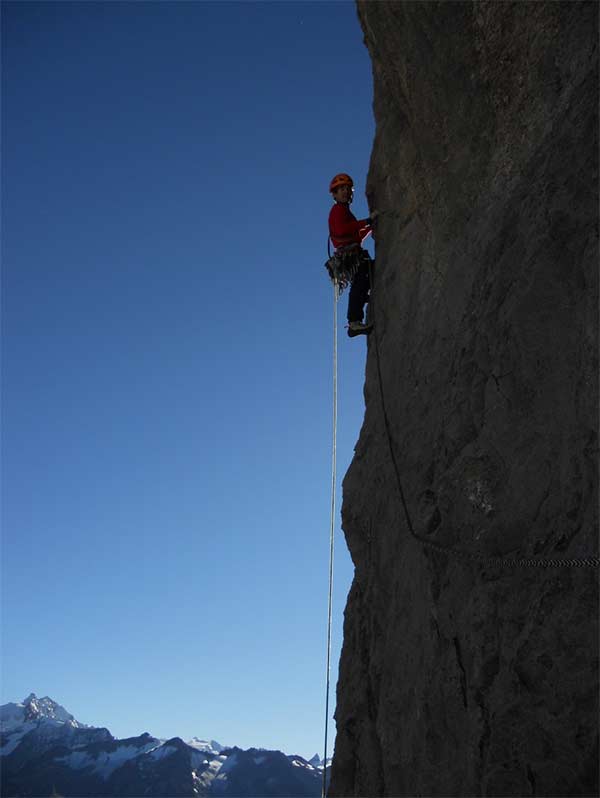

Fixed exes tend to hang on difficult routes, so strong climbers are usually affected. Where does the lack of awareness come from?

I can only guess. On the one hand, there are many climbers who "grow up" in the hall and quickly become strong. The material is regularly maintained there and cable breaks are hardly an issue. When they do go outside at some point, they are often unaware of the danger. Just because you've become strong doesn't automatically mean that you really have experience in these things.

Another explanation that seems just as plausible would be the following: It is more the experienced and strong outdoor climbers who weigh the safety aspects deeply, for example with regard to the use of a helmet, material or rope, which is needed until the core becomes visible.

Not too long ago a rope almost broke in Nassereith, you reported about it on Estbolt.ch. An experienced climber was affected.

Coincidentally, I had discussed exactly this topic with the security person involved in the incident a week before. Of course we agreed. The example, which fortunately ended lightly, simply shows what can happen and how insidious the whole thing is.

What are specific precautions that climbers can take?

An important point is to deal with the topic: Why is a carabiner sharpened? In principle it is self-explanatory. For example, if you lengthen the sling at points where the rope is clearly deflected, this not only reduces the rope pull, but also protects the affected carabiner. In the best case, you can manage that the safety device is not strained when lowering the climber. In my experience, such a carabiner lasts a very long time.

Carabiners become dangerously sharp when the rope passes through the carabiner at an obtuse angle. To put it simply, you can imagine a round file scraping the quickdraw instead of the rope. This will give you a good idea of the sanding pattern this will leave behind.

The situation is different with the diversion at the stand. But that too is self-explanatory if you take a moment to think about it.

«In simple terms, you can imagine a round file that scrapes the quickdraw instead of the rope. That gives you a good idea of what kind of sanding pattern this leaves behind."

Daniel Benz

Rope tears caused by ground-in fixexes: you can do this

- Take personal responsibility and deal with the topic

- Taking responsibility for others by replacing or at least removing ground-in carabiners

- Use steel carabiners instead of aluminum carabiners

- Fixexes only hang as long as necessary when configuring

- Lengthen exen to reduce abrasiveness

- Stand close to the wall when belaying and lowering

Back to the precaution, what can be done next?

When you've removed sharp carabiners from a route, honest people tend to leave the gear at the start of the route, as you don't want to steal them. Unfortunately, I observed several times that the same carabiners were hanging in the route again a few days later. That's why I now see the removal of aluminum carabiners more as garbage disposal.

Otherwise, something else should be mentioned that has nothing to do with rope tears, but can also lead to a fall: the failure of an intermediate safety device on the first few meters of a route. Permanently installed slings age due to UV radiation. It also happens that the back of the sling rubs on a bump in the rock and the sling loses material strength unnoticed until, in the worst case, it can no longer withstand a fall.

When equipping a route with fixed equipment, I often use rope slings instead of quickdraws. This has the advantage, among other things, that the sling length can be optimally adapted to the circumstances. Compared to the often thin quickdraws, however, the UV resistance should also be significantly better - keyword penetration depth. And last but not least, it is also much more expensive if you hang several quickdraws together.

Ultimately, climbing lives from personal responsibility. In other words: if I use something that already exists, I have to check and assess it myself.

Yes that's the way it is. A whole book could be written about personal responsibility and how this is increasingly being lost in our modern society. Personal responsibility is indispensable, especially in our sport. Nevertheless, mountain sports not only consist of personal responsibility, but also of camaraderie, which automatically means that you not only take responsibility for yourself, but also to a certain extent for your fellow human beings. So if you have the opportunity to prevent an imminent accident, then you should do so, no matter whose responsibility it is, right?

Without a doubt.

An example comes to mind from Sicily, where I could have prevented an accident, but I chose not to do so out of convenience.

tell

In the San Vito Lo Capo climbing area, a whole stand broke out with a slab a few years ago. I had climbed the affected route on vacation years earlier. On the last few meters before the deflector, the rock sounded massively hollow and quite extensively. And it was precisely in this hollow scale that the stand was. Fortunately, I was able to cross to the stand of the neighboring route relatively easily and use it.

I suspected that things wouldn't last, but I didn't have any tools with me, I didn't speak Italian, or I knew anyone from the locals. So I left it at that, assuming that nobody would probably sit in there, because I felt the danger was really obvious.

"So I left it at that, assuming that no one would probably sit in there, because I felt the danger was really obvious."

Daniel Benz

Some time later, a colleague planned to go to that area. He took his drill with him so that he might be able to develop something himself. Since I still remembered the stand in question, I pointed out to him that he should renew the stand after all. I told him casually rather than forcefully. That's probably why he didn't think about it when he was there. And since he didn't climb the route, of course he didn't notice it.

After that, more years passed until finally a person with this stand actually fell and was seriously injured.

Do you blame yourself for that?

No, but I try to learn from such things and try not to repeat mistakes that have happened to me or others.

If you would like to delve deeper into the subject, we recommend the following links:

- Cause of accident: broken rope! | mountaineering

- Fixed exes: convenient but dangerous! | Blog Marcel Dettling

- interface exe | DAV Panorama

That might interest you

- Do you suffer from fear of falling? Here are tips from Adam Ondra

- Another massive rockfall in the Mont Blanc massif | Video

- Simon Wahli seriously injured in crash

Do you like our climbing magazine? When we launched LACRUX, we decided not to introduce a payment barrier. It will stay that way, because we want to provide as many like-minded people with news from the climbing scene.

In order to be more independent of advertising revenue in the future and to provide you with even more and better content, we need your support.

Therefore: Help and support our magazine with a small contribution. Naturally you benefit multiple times. How? You will find out here.

+ + +

Credits: Cover picture Eastbolt.ch