Didier Berthod was a leading figure in climbing in the early 12s, but then retired as a monk in a brotherhood. Now, after more than XNUMX years in the monastery, he made another U-turn: Didi is back, back on the rock! In the next episode of the news show BETA we talk to Didier Berthod about his comeback. At this point we take a look back: In 2016, the journalist Olivier Christe set out to find Didier Berthod, the monk.

A guest contribution by Olivier Christe

My search begins in Bramois, a village in the Valais. "Berthod" is lined up on the mailboxes after "Berthod". I am undecided looking for a clue when a woman approaches me. I ask about Didier. She looks at me in disbelief: "Are you sure?" - "Yes, the climber, the monk." Your features relax. “He doesn't live here. Not in a long time. But come in. "

The Berthods are a big family. Simon, the youngest at the age of a few months and the son of Didier's brother Cyrille, is just waking up. She puts him next to me at the kitchen table and says: “I remember well when Didier Called from Canada in 2006: Mom, today is a wonderful day. My knee is broken. It can no longer stand climbing. I can finally stop doing it. "

My knee is broken. I can finally stop climbing.

Didier berthod

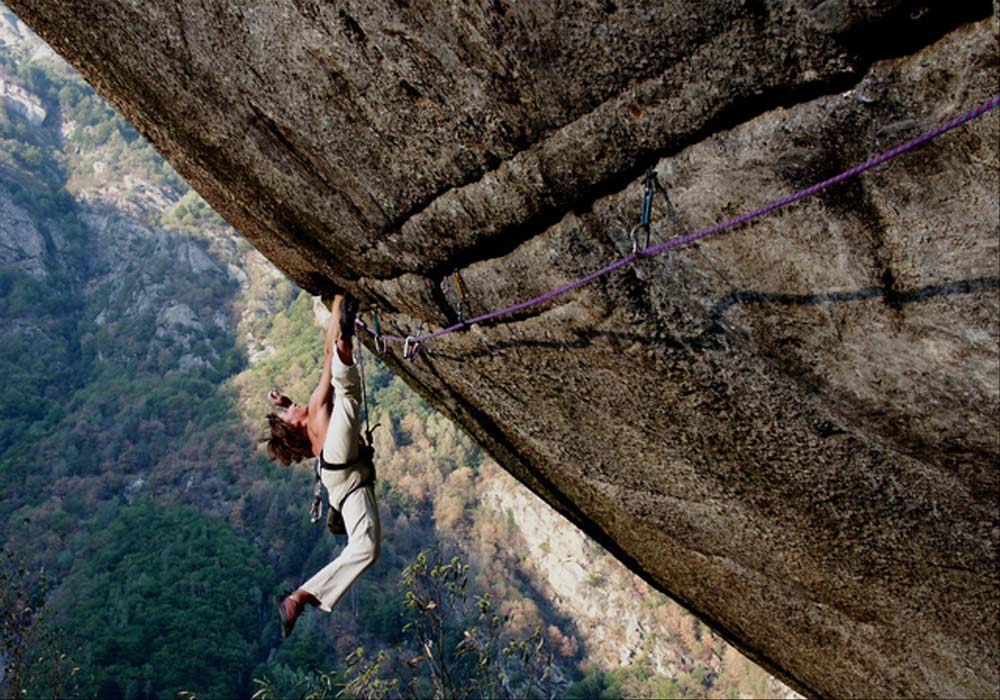

2006 in Canada: A fine crack runs through the overhanging wall. Wide enough that the man can pin his fingers in it and hold it that way. His breathing can be heard loudly. He blows out air in puffs. Then someone from below calls out to him: «O. k., Didi, come on. " The camera moves closer. The climber places a friend in the crack and attaches the rope. The breath takes over again. "Come on," someone calls out from below again. Didi groans. And falls.

The film "First Ascent" shows Didier berthod, then 25, in the previously unclimbed Cobra Crack (8b +) in Canada. For months he tried to crack the route, but he kept falling into the rope at the key point. The knee injury ended this last big climbing project of the exceptional Valais expert prematurely. At the end of the film, Berthod says to the camera on crutches: “Climbing led me to this life: traveling, little money, simple things. It made me feel like I was alive. " And then comes the information that Didier is now recovering in a monastery in Switzerland.

Climbing led me to this life: travel, little money, simple things. It made me feel like I was alive.

Dider Berthod

Immediately after his return, Berthod entered a Franciscan brotherhood. But what the film suggests as a place of recovery before returning to the rocks is a turning point in Berthod's life. He seems to have detached his gaze from the rocks and continued to turn towards God towards the sky. Ten years have passed since then. His knee has recovered, but he stopped climbing. The search for God now fills his days. What did he find?

"I wanted to experience great things"

Back in Bramois. The whole family comes together for lunch. The parents say a short prayer. The salmon tastes great. Father Berthod then leads me through the wine cellar. With two bottles of wine, I get into the car with Didier's brother Cyrille, who is driving to Bern. I want to know how it was growing up with Didier. We are only slowly returning to the past. Mores, Martigny.

Ultimately, the climbing trips for young people help: “Once we ran out of money. Didier should buy some food. Instead, he returned with a pack of M & Ms and the explanation that an old woman needed the money more. " The indignation of that time can be seen in Cyrille's gaze. "Look at me. I need food." Today's mountain guide draws attention to his powerful body.

It was before the cell phones. We were free. Sometimes we had to help in the vines. Otherwise we hardly had any obligations.

Cyrille Berthod

«Didier was more talented, quickly better, after two years he climbed 8b. We traveled a lot together in those early years. First in Valais. Then to the surrounding countries. It was before the cell phones. We were free. Sometimes we had to help in the vines. Otherwise we hardly had any obligations. "

The freedom from then stuck with him. He looks carefree. And Didier? “Today I wonder what was going on in him then. Now he always talks about being sad. He's talking about this Cobra crack. And then he says that he has finally found his rest with God. But ask him yourself. " Aigle, Vevey, Bull. Cyrille drives me to the brotherhood near Freiburg. Unfortunately he had to go on straight away.

The brotherhood is idyllically situated on a hill and is affiliated with a Christian anthropological school.

Didier berthod

The 35-year-old from Valais belonged to the global climbing elite until 2006, but then decided to live in a Franciscan brotherhood. Today he no longer climbs.

Due to the semester break, the house is orphaned. Only the gardener is there, she offers me a coffee. Everyone is on a walk together. Suddenly I hear a laugh from outside. The gardener is describing to Didier my journey via Bramois. He looks at the wine. "Was Cyrille there?" We greet each other.

Not much is left of the strong body.

The man is short, skinny. The hands are fine. The laughter in particular is reminiscent of the climber from “First Ascent”. Not much is left of the strong body. A brown robe and a white cross hang over it. In one of the empty classrooms I ask him why he was sad. Didier doesn't need to go back to the past. "In my children's room there were pictures of the climbing stars of that time: Chris Sharma, Alex Huber ... do you know René Girard?" I deny «A French anthropologist. As I read it, I realized that at the time I had mainly imitated. I lacked an identity. "

I am amazed. That should have been the mourning: the heroism of a 14-year-old? Didier says no: “But it was already there. I wanted to experience something big, and for that, so my conclusion at the time, I had to become someone big. Climbing got me there. It took me to places where I felt part of a whole. It gave me an identity. "

Not only his sporting achievements, but also his ethical convictions made Didier Berthod a leading figure.

Claude Remy, himself a climbing pioneer, writes about the "Berthod locomotive, which became the leader of an entire generation of climbers". Not only his sporting achievements, but also his ethical convictions made him a leading figure. He climbed the most difficult routes almost exclusively secured with friends and wedges, which made him a pioneer of an emerging ideal: leaving no traces and still climbing as difficult as possible.

Love for the world and for life

But when he believed he had finally developed an identity, a strange feeling arose: "I saw myself in a magazine for the first time and was shocked." He was imitating the image he saw of himself there. «Climbing became more and more an addiction. I reached my limits with the Cobra Crack. It was just about getting better. " His life revolved around these 20 meters of rock. “Then my knee released me and I knew that I would no longer climb, that I would not return to this grief. Life in the brotherhood does not know this grief. "

Climbing became more and more an addiction. I reached my limits with the Cobra Crack. It was just about getting better.

Didier berthod

But what is it then? “Above all, a return to the love I lost as a climber in recent years. Love for the world and for life. And it is the imitation without the need to become better than the imitated. "

Didier pursues this goal here: four hours of prayer every day, studying theology and living closely with his brothers and sisters. On the other hand, he has completely renounced interpersonal relationships since joining, and his last visit to Bramois was also ten years ago. Why? “Sometimes I feel sad when I think of my little nephew Simon. When I imagine how he laughs at the crowded kitchen table. But I pass on life differently here.

Little is left of the strong body. Above it a brown robe and a white cross.

I am the contact person for the male youth at the school. I try to help them out of depression and addictions by using my own climbing experience. It's about constant joy in life. " Didier goes into his room and takes out a book: "Le soleil se lève sur Assise" by Éloi Leclerc. "I read it when I was 16, at 20, at 25 and most recently a few days ago." He drives me into town on his scooter, where he is attending a lecture. I get on the train and into the world of Éloi Leclerc.

The author tells of his experience in a German extermination camp. He asks himself whether evil is already inherent in man. He finds the answer in Francis of Assisi, who puts all beings and appearances, not just people as in later humanism, on one level and thus prevents someone or something from being degraded and legitimately tortured, injured or destroyed as a result.

He reduces material possessions to an absolute minimum. It's a utopian hymn of love. Christian flower power mixed with communist values. Despite the shortcomings, it doesn't leave you cold. The desire for mutual respect is too urgent. And Didier's life clearly bears this signature: the story with the M & Ms, the attempt not to leave any traces, the love of nature and the great gratitude.

Didier the exorcist?

A week later I met Didier again and asked him about the utopian features of the book: "Unlike Francis of Assisi or Leclerc, I do not assume a paradise on earth," replies Didier. Instead, he builds on the hereafter and is satisfied with fighting injustices here: «It's all we can do. I wouldn't take all this effort to live here forever. "

His studies will end in a few months. He will continue to specialize in casting out demons. Exorcism. I get all the warning signs. He tries to calm down and explains the process: "Praying together with those affected over months or years to drive away the demons." I try to translate. Is it a mental illness? Is praying together a form of meditation? The images of flushes and screaming fits disappear again, but somewhere between paradise and demons I have lost Didier.