The ring bands (Ligamenti anularia) are heavily loaded, passive structures, especially when we raise our fingers when climbing. Accordingly, climbers often injure the ring bands. In today's post, Klaus Isele explains what the symptoms and reasons are and how you can prevent injuries.

A contribution by Klaus Isele - physiotherapist, osteopath and climbing trainer - with the support of Black Diamond

The ligamenti anularia (ring bands) are heavily loaded, passive structures, especially when we raise our fingers when climbing. The fingers are flexed using two large muscles, the contractile parts of which begin at about the elbow. The force is then transmitted to the finger joints via long tendons. My experience from many years of work as a physiotherapist shows me that only around a third of the cases of climbing-related finger complaints really affect the ring bands.

When does a ring band injury occur?

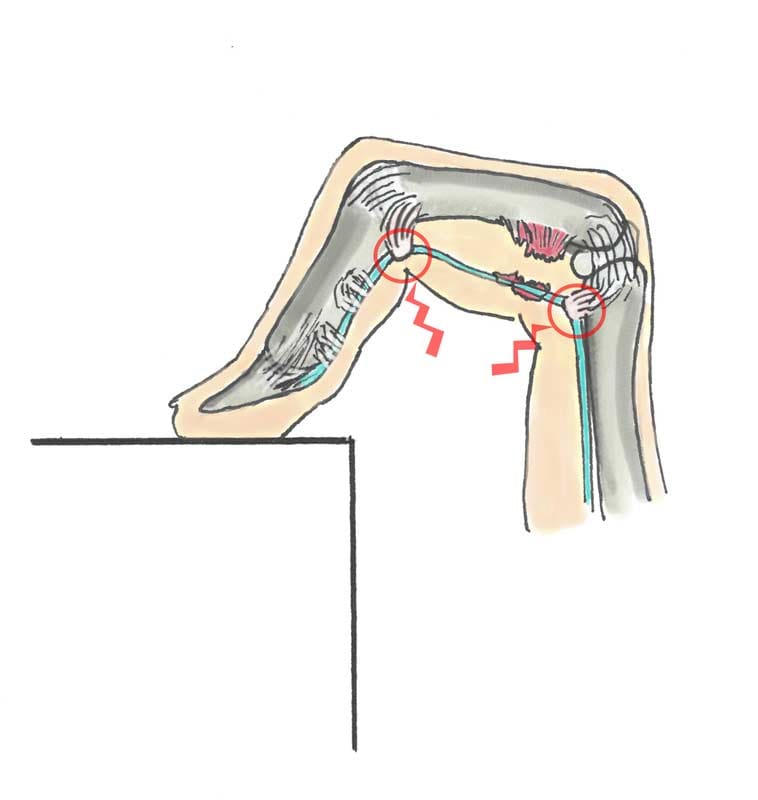

The most common occurrence of a ring band tear is when a full finger (e.g. ring finger) is placed under maximum load eccentric force come in addition.

Here's an example:

You hang your fingers on a small bar with your right hand fully raised. While you want to pull yourself up with your right foot and right hand, the little kick suddenly breaks out. This leads to an eccentric overloading of an already fully loaded ring band and consequently to a ring band rupture.

The second most common risk is concentric overload. Simplely explains: You crimp as much as you can and try to pull up dynamically. This leads to the typical snap and the ring band is off.

Symptoms of a ligament injury

Acute rupture

- Pain in the affected area

- Swelling in the affected area

- Sound

When a ring band breaks, there is often a loud "snap", a mostly audible "plop sound" or a sound as if something breaks. Sometimes there is a crunchy, scratchy sound. In such a case, it often affects other structures, and it can be partial ruptures.

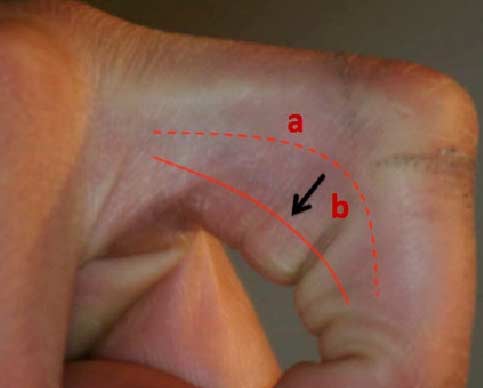

- Bowstring

The loss of one or more ligamenti anularia leads to the “bowstringing phenomenon”. This “tendon lifting” is the typical guiding symptom of a ring ligament rupture.

This phenomenon can be determined by palpation, performed by an experienced physiotherapist. It is also possible to measure the distance between the tendon and the bone using ultrasound or with a caliper in a left-right comparison.

Sign of a ligament injury

A prehistory that I've heard in my practice several times: "It was the last chance, I was so close to scoring my project and that's why I canceled the two rest days to give everything on the very last day of vacation." As a climber I understand that completely, but as an osteopath I have to say that the greatest risks are involved. Especially in combination with group dynamics, we quickly overlook the first signs that have already appeared a few times, such as:

- Slight finger pain after climbing / bouldering

- Areas of attachment of muscle groups of the arms hurt a little

- Coordinative fatigue (there is no such thing, I can always make this simple jump from the warm-up boulder immediately)

- Longer swelling of the fingers after the units than usual

Most patients with finger complaints can logically explain retrospectively why this happened.

Examples:

- That was the second intensive session of the day

- I actually had a mild cold

- I was finished with my unit when a friend was still driving me

- I had a tear in the ring and was not allowed to climb for a long time from the doctor, but now I can and have suddenly done too much

This is how you prevent a ring ligament injury

Be smart and know when it's enough. Group dynamics are great for training, but can also be dangerous. In addition, an individually customized warm-up program is essential, as is good warming-up after the sports session.

- Warm up: Find your personal warm up program. Which type are you? Do you need a particularly long time to warm up? Then take your time! Are you getting tired after 50 minutes, is your focus and coordination waning? Then choose your time slot differently.

- Warming up: Gradually reduce the load that you have built up during training. Afterwards I recommend to stretch a little and eat a little something after the workout. Use the glycogen window for this. A yogurt drink and a banana as a “post climbing snack” are particularly good here. Liquid is quickly absorbed, sugar, some fat and proteins with minerals help you relax your muscles (plasticizers, ATP) and fill the glycogen stores quickly.

- Avoid completely erected finger position: I personally do not recommend not doing this. Depending on the area in which we are climbing, it may not always be possible to avoid setting up, so it is good if our fingers are used to it. But think about whether you want to "pop" all the bars at the end of a training session in a tired state = I and the signs mentioned above for the ring band tear are critical.

- Do not climb when you are tired: Yes, of course, they are all so easy to write, the therapists and physios. Then how do we get better? And what is tired anyway? Here is a brief digression: "Skilled people make hard things look easy", one of my professors once said. It often looks as if the World Cup climber suddenly falls down without any clear signs of fatigue and then arrives at the bottom and says how finished he was. Professional athletes can access an extremely high level of coordination at the maximum. This is not luck, but an acquired skill from years of hard training at the limit. If I want to push my athlete, I have to be able to demand maximum coordination in this state. However, I support the veto of the mature athlete: an athlete who feels good about himself tells the coach if it is too much and it is not possible today. And then it's done.

As a result, you are tired when coordinative qualities are already weakening. You have to see that for yourself. A coordinative boulder that you take as a test might serve as a reference. - Stop in case of pain

- Beware of rapid progress in difficulty. Tendons and ligaments develop more slowly than the muscles. Yes it is true, muscles can build up very quickly, passive structures such as tendons and ligaments take much longer! But I want to get better ... and quickly. Coordination, learning movement patterns, playful bouldering, like we do, for example Udo Neumann show up - this is very important training. And the ring bands do not reach their limits. Specific strength training should be simulated to the technical training. Climbers who previously built up strength in the gym often lack the flexibility and awareness of their bodies on the wall. In the eighties, some climbers experimented on their own by trying to climb better by building muscle (hypertrophy). The outcome was clear: everyone got worse because they lost mobility and gained mass. Well, don't trust any study that you haven't faked yourself. If you observe the development of athletes nowadays, for example in the World Cup, a big biceps is already a trump card, like a national coach Urs Stoecker asserted.

This is how professionals like Adam Ondra, Janja Garnbret and Akiyo Noguchi warm up

About the article series

The series of articles with Klaus Isele takes up climbing-specific health topics at regular intervals. The series of topics is presented by Black Diamond Equipment.

About Klaus Isele

Klaus lsele, MSc DO, is a climber, physiotherapist, osteopath, state-certified trainer for sport climbing and has accompanied the Austrian national climbing team for ten years. He also looked after for two years Adam Ondra, whom he supported in climbing the first 9c, among other things. Klaus runs the practice Therapierbar with four branches and follows a clear approach: A lot can be treated, you just have to know how.

More about training

That might interest you

+ + +

Credits: sketch Daniel Zimmerman